Reigning (raining?) confusion: what is figurative realism?

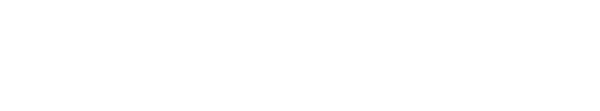

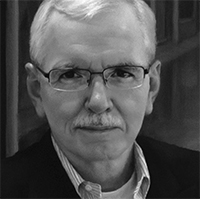

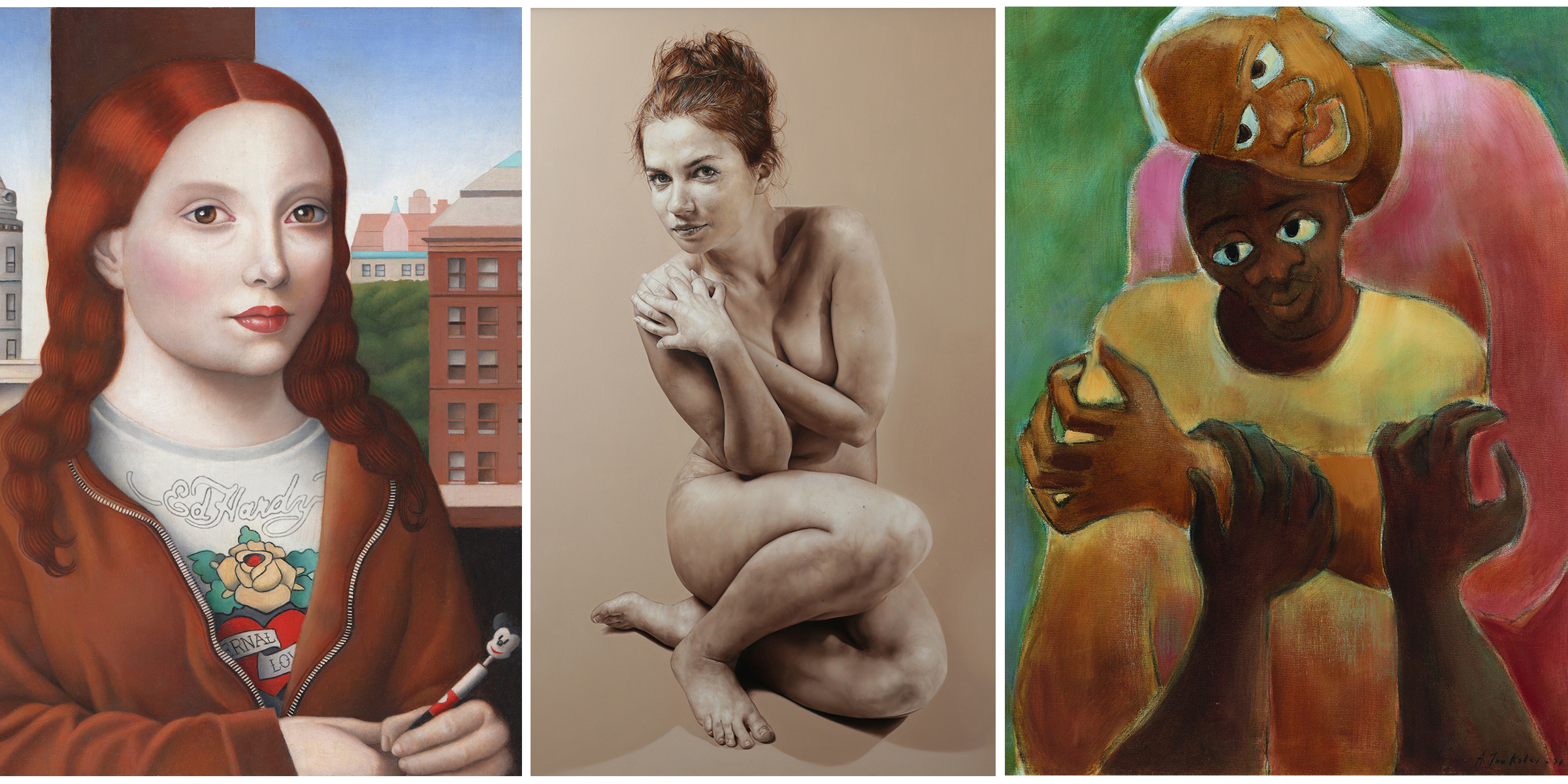

L to R: Artist: Amy Hill, Woman with Mickey Mouse Pen; Artist: Anna Wypych, Grey; Artist: Ann Tanksley, The Smothering Mother.

As co-founders of The Bennett Prize for Women “Figurative Realists,” Doctor Schmidt and I often confront confusion about the meaning of “figurative realism,” especially among would-be contestants. “My work is too abstract,” one will say, while another says “the Bennetts only support photorealism,” and a third says “the Bennett Prize seeks only depictions of nudes.” Of course, all of this is incorrect, but you can hardly blame the authors of these observations, as the lack of understanding of the term “figurative realism” is extensive.

“Figurative realism” is a compound term comprised of two words with overlapping meanings. “Figurative” is basically what the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art Terms (Oxford) says it is: “an adjective used to describe art which represents the human figure by means of a figure, symbol, or likeness.” The key point for us in using the term “figurative” is that the work depicts a human figure or figures, of any gender, clothed or unclothed, where the figure or figures are central to, and a principal focus of, the work.

As for depicting figures with symbols, “symbol” in the Oxford definition does not mean that you may substitute a bird or a full moon or a flower for a human. Rather, it refers to “Symbolism,” the practitioners of which believed that another world lies beyond (or behind or beneath) the world of appearances and who tried to depict this world in their work. No matter. For us, if your work can show one or more human figures, discernible as such, while at the same time implying that there is another world beneath the surface, go for it.

As for “realism,” it is the more difficult word, both in terms of what it means and the continuum of work that it defines. Generally, the term is understood to mean “art which depicts something that is clearly identifiable as such.” More commonly stated, “realism” seeks to depict things as they “appear.” The problem is with the continuum. Where does “real” end and “abstraction” begin?

At one end of the continuum is “photorealism,” art that seeks to depict objects or figures with the level of detail one would find in a photograph. Akin to that is “hyperrealism,” which takes photorealism one step farther and accentuates details beyond what the eye would normally see. Of course, either of these is within the definition of “realism.” The problem resides at the opposite end of the spectrum: where is the point at which a depiction is no longer “real?”

For the Doc and I, we are not fundamentalists on the question of what is realism. Without overstating it, we believe that if you can tell what it is then, generally speaking, it’s “real” enough. By way of example, Marie Laurencin’s washed out female figures holding guitars or flowers are “real.” Ditto for Van Gogh’s rough-hewn portraits or Dorothea Tanning’s surreal depictions of women in ambiguous and dream-like settings.

But, you ask, is there a limit? While, for The Bennett Prize, the answer will always reside with the jury, it would be our view that Willem de Kooning’s Woman III is outside the definition of figurative realism, as would any of Angu Walters’ Prayer pieces, even though all of these works nominally depict human figures. What about Picasso’s 1932 masterpiece Girl Before A Mirror? Also too far. Is the girl a mutant, a robot or an alien?

But anything this side of that? Likely enough to get you there. What is “this side of that?” Intentionally, it is undefined. But, for the purposes of example, we urge you to take a look at the work of any of the finalists for the first Bennett Prize.

They stretch from “hard realism” to work that is significantly less so. For the purposes of The Prize, all of the chosen work was “real enough.”

You might also take a look at our Collection, where a photorealistic piece like Anna Wypych’s “Grey” can live comfortably alongside Ann Tanksley’s “Smothering Mother” or Amy Hill’s “Woman with a Mickey Mouse Pen.” For us, these are all “real,” even if they stretch the idea of depicting things “as they really appear.” https://www.thebennettartcollection.com

Bottomline: you don’t have to be a photorealist; if you depict figures in a moderately “real” way, what you’re doing is likely to qualify….